By Rose O. Sherman, EdD, RN, FAAN

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence then, is not an act, but a habit.” Aristotle

Much of what we do in our personal and work lives is a series of habits, both good and bad that we develop over time. Charles Duhigg, an investigative reporter for the New York Times, has written an interesting evidence-based book about how habits are formed and what we can do to change them. Duhigg contends that habits make up 40% of our daily routines, whether at work or at home. What you see in your work environments is in a sense a collection of habits that develop over time. Habits are the brain’s way of saving energy. Yet, not all of our work or personal habits are good habits. If we want to replace bad habits with good habits, we need to be intentional whether it involves losing weight or getting staff to wash their hands before they enter a room.

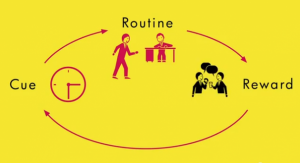

The Habit Loop

Duhigg suggests in his book that habits develop over time through what he describes as a habit loop. This is a three step process deep within our brains that begins with a cue or trigger that tells our brains to go into automatic process, and which emotional, physical or mental behavior to use in response to this cue. The final step is the reward that we feel from the behavior. There is another important aspect to habits. Your perception of the social norms that govern you and how your behavior fits into those norms also influence your habits.

Case Example

Sue Morris is a new graduate nurse working on your unit. Natalie Cody is an experienced charge nurse who is technically very competent but has a reputation of being a bully. Your unit has just implemented walking rounds. Sue is attempting to give report during this walking rounds, but is unsure of her assessments. Sensing her hesitancy, Natalie sees this a cue and immediately begins questioning Sue in an antagonistic tone about the care she has given her patients and her lack of organizational abilities. This discussion takes place in front of whole team who react to this discussion with amused looks on their faces. Natalie’s reward in this situation is a sense of power and superiority. The culture on the unit where Sue and Natalie work is one in which this disrespect among co-workers has been tolerated. A new manager has recently started on this unit. She has spoken to Natalie about what she has observed. Natalie is shocked when her manager tells her that she has a habit of bullying. The manager tells Natalie that she will work with her to break this destructive habit.

Breaking the Habit Cycle

When you look at changing habits, you must not only examine the habit from the perspective of the habit loop but also consider the context in which the habit occurs. Duhigg suggests a golden rule to change behavior. When breaking the habit cycle, you need to look at the routine or response part of the habit loop, while trying to keep the reward. So using our case above as an illustration, the cue for Natalie’s behavior is the insecurity or hesitancy of the new graduate. Her reward is a feeling of superiority and positive feedback from her co-workers. The new nurse manager works with Natalie to change her response from bullying to coaching. At the same time, the manager considers the context of the unit. She advises staff that their unit will have a no bullying culture. Nursing staff who don’t stop bullying when they see it will be considered as guilty as the perperators. The positive coaching of new graduates will be a new core value. So over time, Natalie and her manager work on changing her habit cycle in the following way:

Cue – the hesitancy or insecurity of the new graduate

Response – shift from questioning in an antagonisitic tone to supportive coaching and concern

Reward – the nursing staff who observe Natalie will give her positive feedback about her great coaching

New habits require extensive practice. To be successful in this habit change, Natalie would need to believe that change is feasible. We are all creatures of habit both good and bad. Duhigg makes the case in this important new book that changing just a few key habits (1-2) can make us more disciplined and increase our willpower. The same ideas can be applied to our work settings. When you think about it, the character of a work unit or an individual is a collection of thoughts, values and habits. Work habits developed over time offer a level of comfort but may not be constructive in the complex changing health care environment. It is only through the intentional evaluation of our habits that we are able to change. Understanding habits is an important leadership skill. Duhigg suggests “once you see everything as a bunch of habits….it’s like someone gave you a flashlight and a crowbar and you can get to work.”

Read to Lead

Duhigg, C. (2012). How to Break Habits. You Tube Video

Duhigg, C. (2012). The Power of Habit: Why We do What We do in Life and Business. New York: Random House.

[amazon asin=1400069289&template=iframe image&chan=default]

© emergingrnleader.com 2012

LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram